Asphalt, Iron, Concrete,

curator: Ella Kalir-Ariel, Ella Gallery, YeminMoshe, Jerusalem

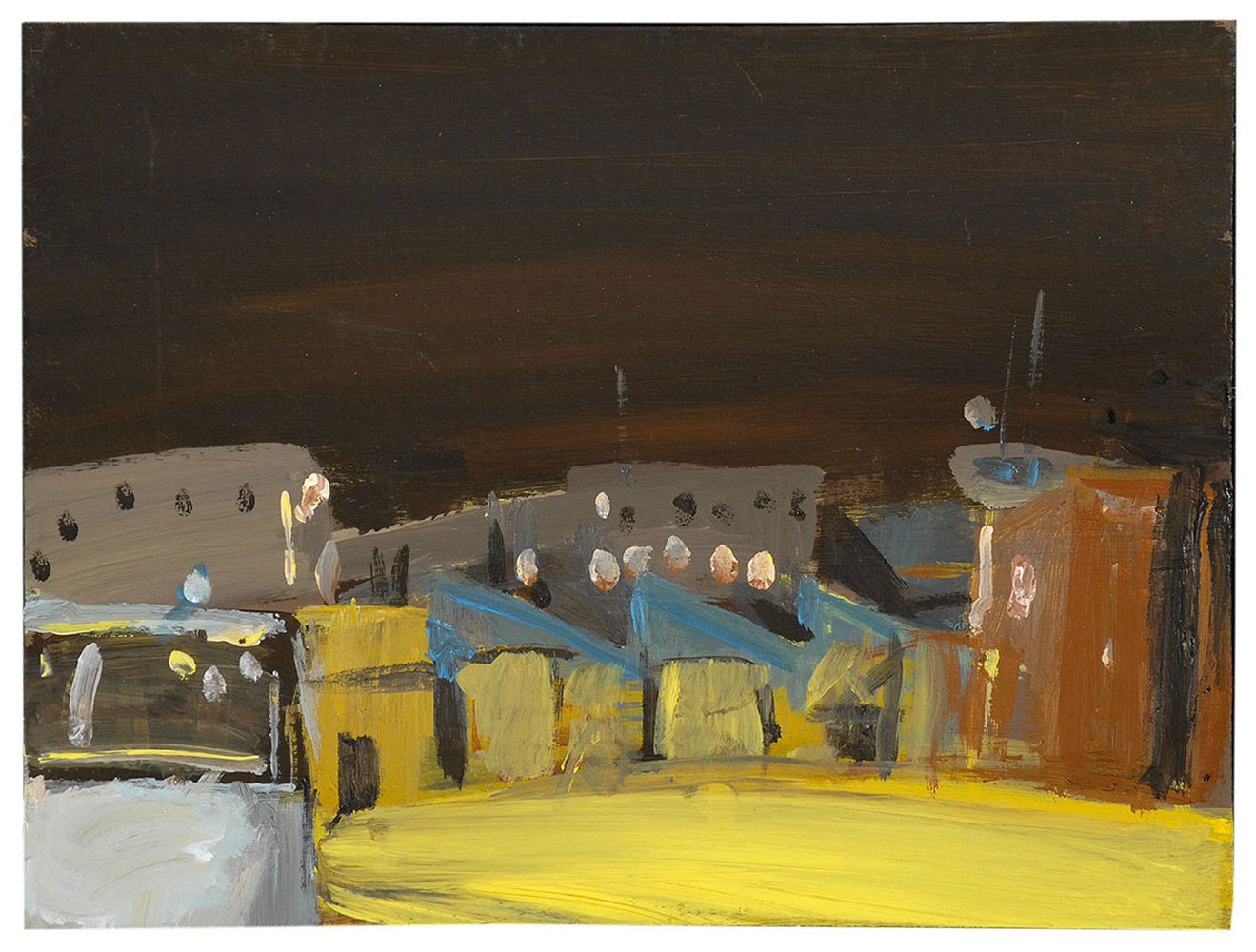

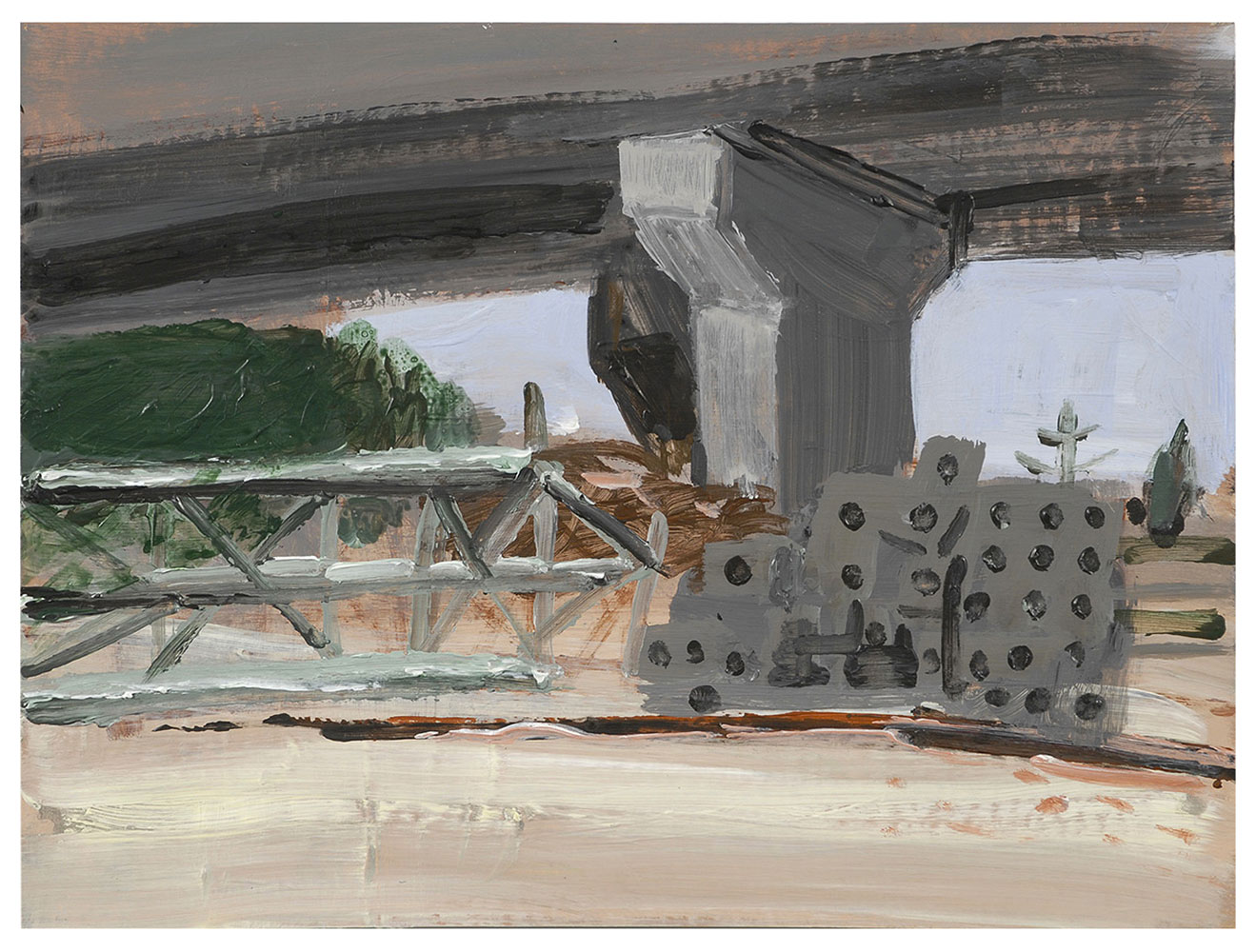

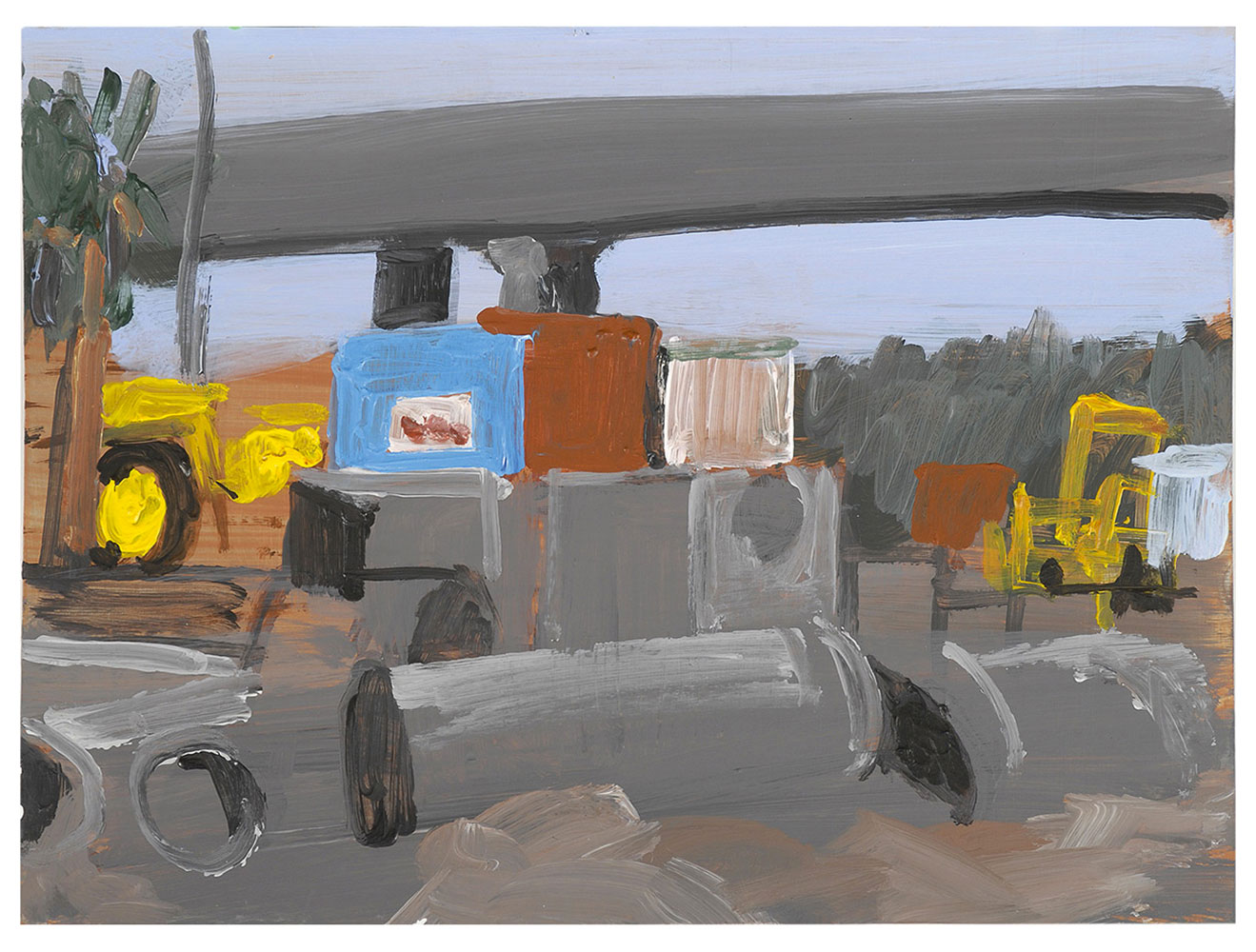

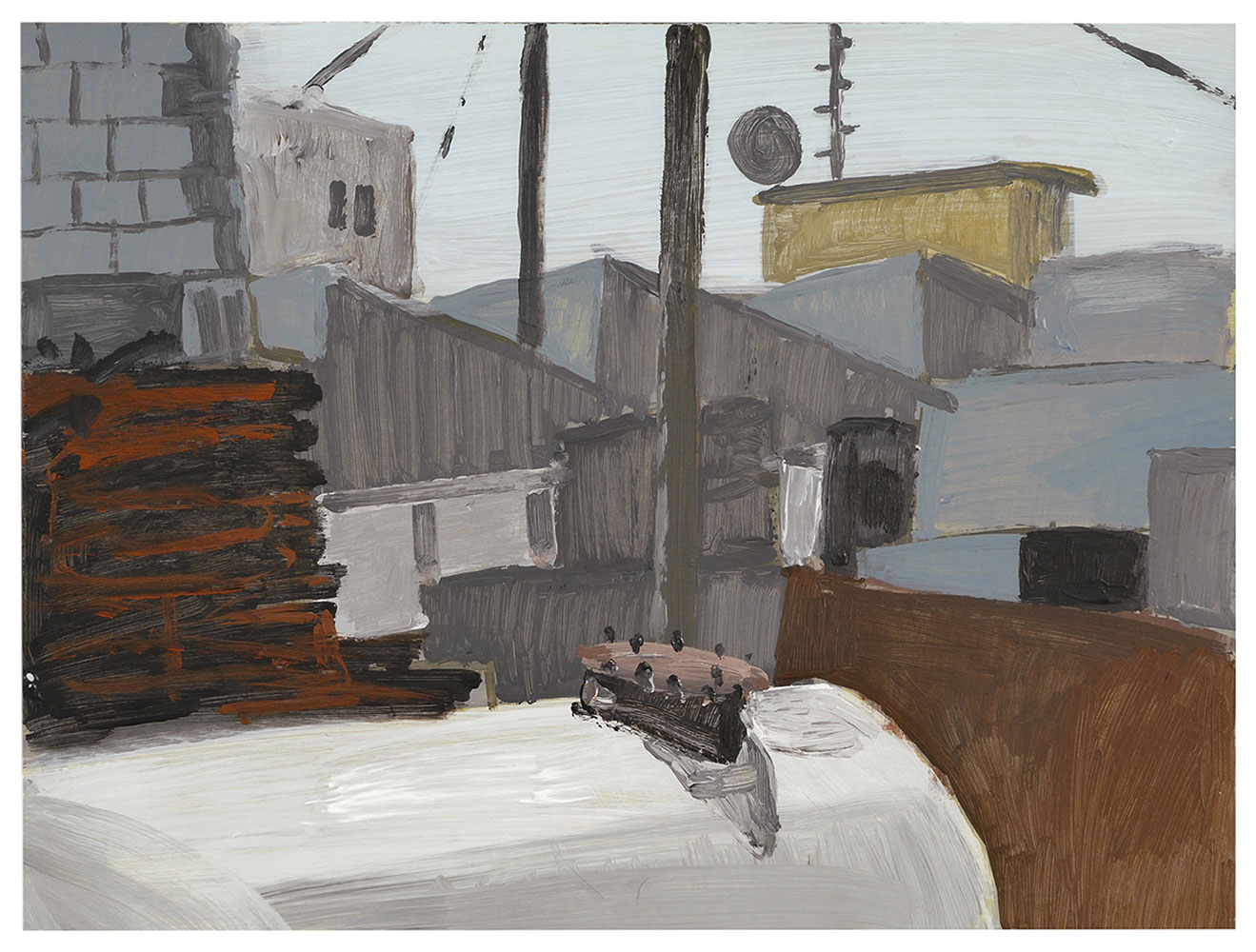

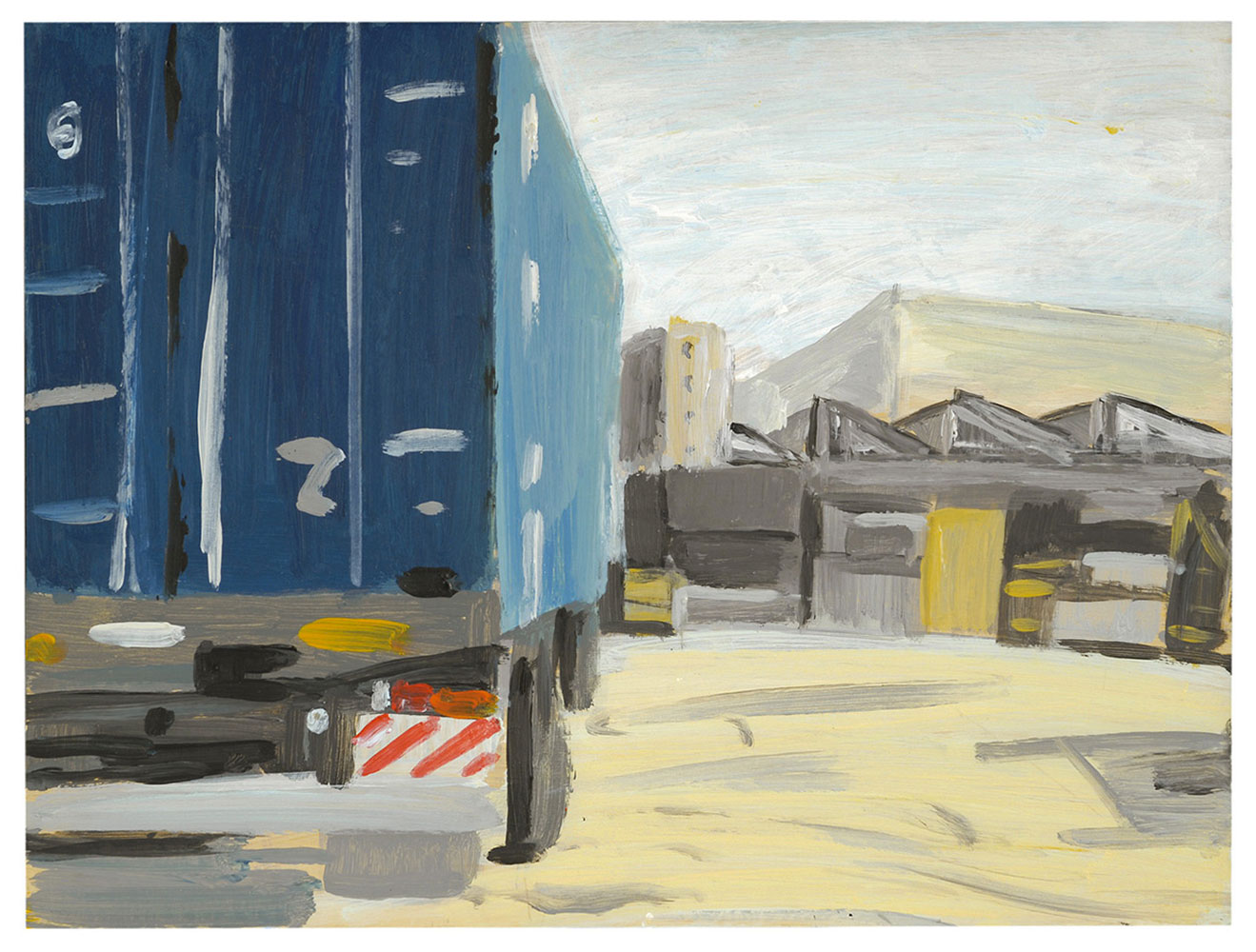

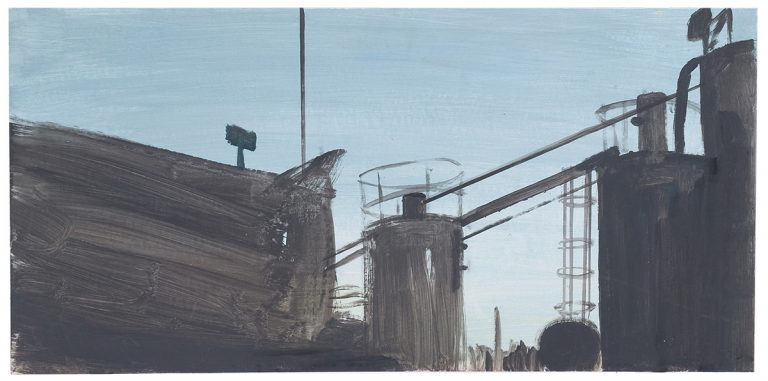

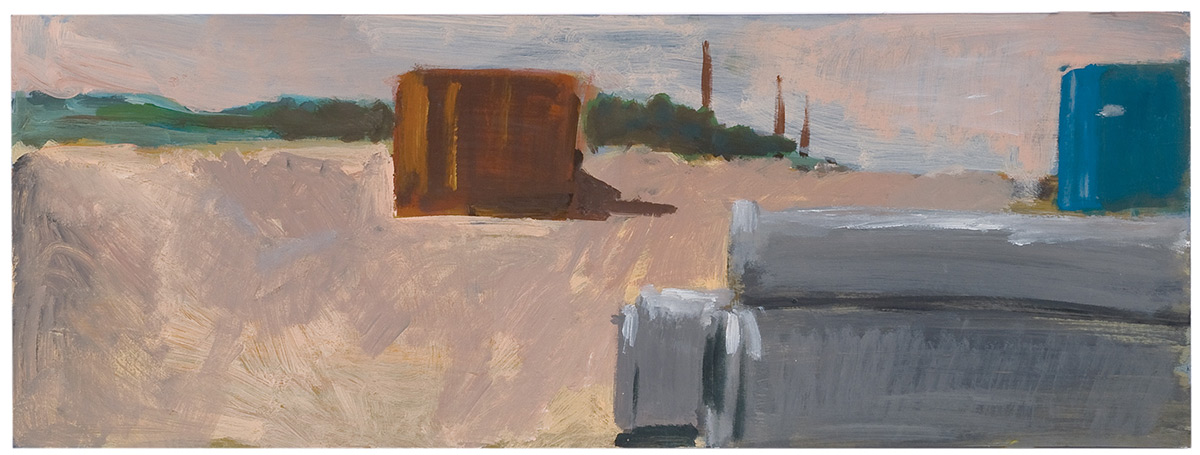

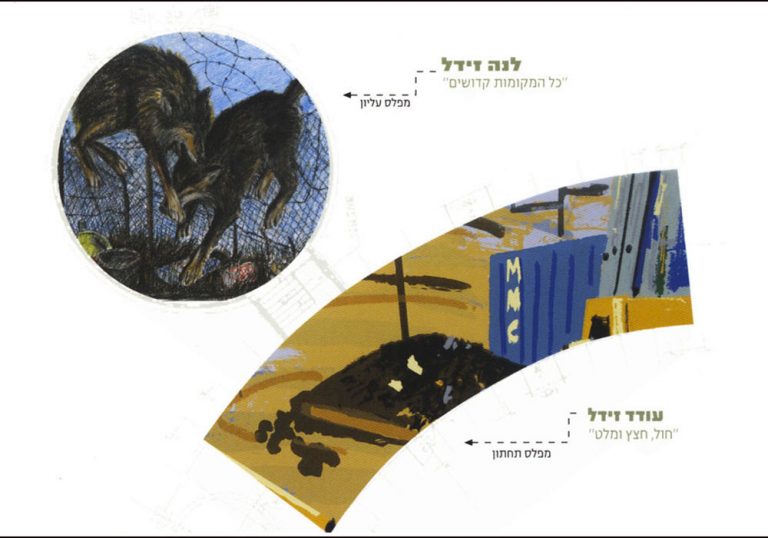

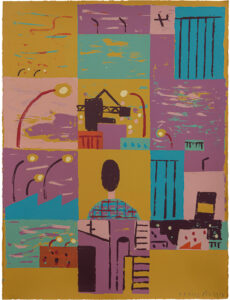

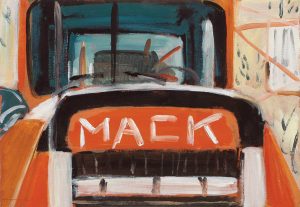

Factory yards, construction sites, scrap metal yards, containers and trucks, sheet metal, pipes and planks. Oded Zaidel paints the backyard of the cityscape. Not natural landscapes or “civilized” city views but marginal zones, derelict corners and places we pass by almost without seeing them. The paintings are usually based on photographs he takes that serve him as a primary sketch. In the work process, the data in the photograph are taken apart and built anew—details in the landscape are blurred, some disappear, until sometimes only a loose connection remains between the painting and the photo that was used as its starting point.

All paintings are devoid of animals or humans. In this respect, one can see Oded’s paintings as a link that developed—in its unique way—from Italian Giorgio de Chirico’s formidable empty city paintings, as well as from American Hopper’s paintings of empty spaces that use a similar space distribution. It was Hopper who said, “An empty room was always a challenge for me… what an empty room looks like when there’s nobody in it… this absence can attest to presence”. There isno alienation in Zaidel’s paintings—the absent person is present, and the truck, the tractor or the crane, the guard booth and the light in the window are evidence of their existence and being about. In this respect one can go back fifty years, to Avraham Ofek’s paintings of agricultural machines in the kibbutz—always unmanned. The junk machine as a subject in some of the paintings, the treatment of the landscape as a random conglomeration of objects and the reliance on photographs, is reminiscent of Larry Abramson’s drawings of mounds.

The seemingly arbitrary, inane choice of subjects, makes the painting itself the subject and focuses the viewer on the language of the painting, the colorfulness, the structure, the division of space and the painting action. Oded’s paintings have warmth, solid ground and sky, daylight or lamplight at nights. Only that what we have on our hands is not a pastoral landscape but construction and industrial sites, the attraction of which lies in dynamism and surprise, just as in the artistic work itself. Using concise language and hearty daubs, he creates solid color planes. In the daytime paintings, the colors are illuminated, dazzling, and seen in all their might, so that one can feel the intensifying heat emanating from the exhaust pipes of the bulldozers and forklifts. In the nighttime paintings, the lights shine and create a dramatic appearance out of a building’s wall, door or window, while darkness covers the dust, the tired watchman inside, the waste and the tar-stained soil.

Ella Clear Ariel, curator

Paintings from the exhibition, untitled, acrylic on cardboard, 30X40 each, 2006

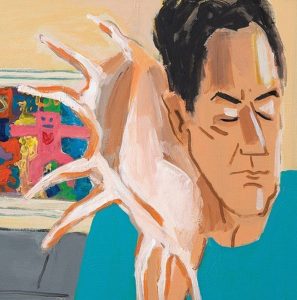

Pictures from the exhibition’s opening, February 2008, Ella Gallery, Jerusalem

Sand, Gravel and cement

Curator: Monica Lavi, August 2006, Al HaTzuk Gallery, Netanya

Oded Zaidel introduces paintings and reliefs from the last couple of years. His paintings and reliefs—in various formats—portray the outskirts of urban areas, industrial areas and construction areas with their cement mixers, cranes, industrial buildings, tractors [or bulldozers], and trucks, as well as various urban images—building facades, lampposts, roads and cars.

Zaidel’s painting style is characterized by broad quick brush strokes, accurate with urgency, delight and confidence. In many ways, the painting is the subject. The color tones, the composition styles, the control over the secrets of perspective—all of these are manifest. Zaidel’s works refer to the Israeli painting style of the early 1980s; especially the color saturated ones of Gabi Klezmer and Yitzhak Livne, who burst into the Israeli painting scene after years of conceptual aridity. Seemingly, this is anachronism, but in fact, it is an act of revelation. Zaidel, now in his forties, began painting three years ago and never looked back. It is of interest to follow the process of one who studied graphic design in Bezalel in the 80s, and twenty years later has returned to the Art Department and its former teachers. The starting point—when one begins painting—can be chosen. A second round turns out to be plausible, optimistic news for all those who hesitate jumping into the pool of the arts.

Illumination is a motif in Zaidel’s paintings. Be it natural or artificial, sunlight or street light, illumination is present at all times. From illumination, shadows are born, and the play of shadow and light creates a drama within Zaidel’s landscapes. The sense of drama that gradually arises from the paintings is accented in face of the dryness in which they are painted and the supposedly offhanded feeling of the subjects. That is because Zaidel creates dramas without being dramatic. He succeeds in touching loneliness without becoming pathetic, and deals with death without saying anything about it straightforwardly.

The human form is supposedly absent. Zaidel’s landscapes are stage sets lacking a protagonist, whereinexists an apparent sense of vacuum and tension evoked by the deserted landscapes. Only that human presence does enter the paintings via formalistic hints. For some paintings, a lateral narrow and long format was chosen, resulting in a somewhat claustrophobic feeling, threatening and even morbid. If the vertical is a sign of life, the horizontal is a kind of death. The ingathered perspectives invite the spectators to gather into the painting, while at the same time urging them to stay outside for fear of being trapped between walls, fences, and facades that will not allow them to reach the horizon. The sky is usually present in Zaidel’s paintings, bright and lit or dark, menacing and sprawling across the painting. Usually, the road to it is blocked. The paintings strive to reach the sky and the viewer’s gaze is attracted to that spot, only that the sky is an impossible wish. On the way to the sky—the color of which determines the mood of the painting—an obstacle always stands. The road is not open, and one cannot advance toward the horizon. The sky’s expanses are the wide, open, breathing space of the painting, and they are bestowed in small gulps.

Zaidel’s painting originate in photographs. Zaidel takes photos of the sites, later translating them into paintings. It is of interest to follow a process that allows the viewer to observe the artist’s interpretation of reality. Zaidel cleans details and textures out of reality, alters the compositions, and manipulates the “real thing” for the sake of visual cleanliness that borders on abstraction. Zaidel’s cleaning of the landscapes, his ignorance of the human form, the condensation of shapes, the use of Bristol paper and acrylic, all these reveal as much as they conceal. Out of the variety of landscapes, the skies, the industrial areas and the urban buildings, rises a sharp sensation of Israeliness: something arid, lacking beauty in the common sense, which cannot stand surplus emotion and strives for purposefulness.

Monica Lavi, curator of the exhibition at Gallery on the Cliff, Netanya, 2006

Romema-Talpiot

Curator: Doron Livneh, December 2008. Agripas 12 Gallery, Jerusalem

Having learned of Gauguin’s departure to Tahiti, impressionist painter Renoir commented, “Why? One can paint just as well in Batignolles.”Batignollesneighborhood in Paris is just like Romema and Talpiot in Jerusalem and indeed, in Oded’s paintings–as he attests—there is a definite

Read more…

impressionistic trace. He lives the sites he paints in an existential manner, not like a tourist. Oded’s landscapes are not picturesque, not ornamental. Cezanne (although a post-impressionist) painted Sainte-Victoire mountain repeatedly; Monetpainted his garden at Giverny; Renoir painted sailing parties on the banks of the Seine. That was how Giacometti drew Paris.

For the above-mentioned painters, those landscapes were not an Outside: not Tahiti, not Casper David Friedrich’s mountain peaks, norTurner’s turbulent sea landscapes. The impressionists and post-impressionists did not stand in front oftheir surroundings; they internalized them as they frequented them more and more and drew them directly on the canvas, during light hours, without preparatorysketches or underpainting ,as was customary until then. Anyway, that was how the “classic”impressionist paintings were made. The impressionist painting did not stand between the painters and their surroundings, it was not a reproduction of the environment (as were, for instance, Canaletto’slandscapes of Venice and London), nora romantic display of the elements; the impressionist painting was more like the imprint of the environment on the canvas.

The essence of Impressionism is the color, and here two does Oded follow the impressionists. Unlike them, his paintbrush strokes are expressionist in character; his colors create an atmosphere and general lighting slightly more than it is conveying the exact colors of the subjects. A deeper difference lies in the choice of drawing sites. The impressionists drew optimal environments provoking optimism, expressing the course of life, “nature” in the positive, idyllic sense (nature derives from “childbirth” and “growth” in Latin),while present at Oded’s sites is the threatened, the empty, which stands in contrast to the body’s wellbeing and a fertile and constructive lifetime. Oded shows the violencethat humanity implemented on “nature”by way of the industrial revolution. His paintings have what the body cannot bear in its free movement, with breathing. Here there is no relaxing sailing on calm river waters, but the aftermath of the actions of bulldozers. These are landscapes of the Waste Land; remnants of civilization and its ruinsleft by humanity. Here, human presence is of abandonment, not of coming together and mutual benefaction of humanity and its surroundings. What we therefore have is forgotten landscapes. This forgetting emergesbefore our eyes in Oded’s paintings.

Left in his landscapes are temporary shelters and means of protection—means of cutting and dissecting the environment such as fences, railings, canisters, containers, structures in the process of being built or demolished, and industrial sites bereft of human presence.

Eventually, the main impressionist message is the intimacy of a person in what he sees—an intimacy in contrast with remembrance and commemoration. This sense of intimacy arises also from Oded’s paintings—Romema and Talpiot are neighborhoods he passes through almost daily, but the difference is this: the impressionist intimacy is that of a home dweller in his habitat, where he thrives, while in Oded’s paintings there is nothing worthy of being called “a home”. This is the intimacy of a tramp, a homeless person vagabonding about like Cain who built the first city after being expelled from Eden.

Doron Livneh, curator of the exhibition at Agripas 12, Jerusalem, September 2008